Educating Stability Table of Contents

Next chapter: Educating Stability: Appendices

To generate greater traction and engagement, one has to break out of the social studies that has passed for schooling and weave three factors together:

Traditionally, there has been a legacy of cultural assumptions that has discounted the importance of individuality relative to one’s host culture. Ancient Greece considered the individual to be subsidiary to culture. More recently, philosopher Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan (1651) believed in the necessary supremacy of government in culture because life in a state of nature was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”39 Believers in the social contract assert that those born into a culture owe their heritage to that culture for the quality of life they enjoy.

Unfortunately, it isn’t safe to embrace a culture and its government without reservation. Ibn Khaldun, (1332-1406), a great Muslim polymath, a sociologist, historian, and author of Muqaddimah, was more circumspect than Hobbes. He described government as “an institution which prevents injustice other than such as it commits itself.”40 It is too easy for a culture to become a user of people. Government, too, can become a user of people.

Neither is culture an ultimate authority. Culture fails with those who do not share that culture’s background.

For safety and effectiveness individuals need a sturdy and dependable framework supported by meaningful education that recognizes it. Past education that people have depended upon has proved no longer up to the task of providing stability. That which has been taught has become overgrown.

Since the 1950s, shaken by uncertainty, education began to repeat what it had always taught only louder. Good teachers need to find a way to nudge students toward the knowledge and processes to work this out.

Traditional education is good at what it does, but what it does well isn’t all people need:

Little consensus has been reached to address essential understanding that is missing, such as:

The three can be summarized this way:

As children connect language and thought, they are empowered and motivated by simple wisdoms that underlie their conversation.

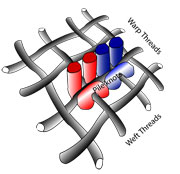

When one discovers that cultures and society are different, it changes the relation of individuals to everyone else. Cultures are like the pile of a carpet, varying in color, shape, texture, length, thickness, and material, while the minimum requirements for society are like the warp and weft of the carpet beneath the pile that hold cultures together.

The warp and weft provide the structure for stitching together society. Without the warp and weft threads supporting the carpet, all that exists is a pile of pile. Nothing else holds the carpet together.

Below we will show humility and reciprocity ar the warp and weft threads. Nudged to see why, individuals will recognize they are worth defending because absent society’s supporting threads citizens risk either serfdom or slavery.

Today, many seem recognize that ethical bases are challenged, but few seem to say so. Look at society. Society doesn’t know why it should be decent. All of the current generation is asking why. Why should I do this? Why should I believe in that?

Society is edge where any two individuals or cultures meet. Society requires no religion, no shared experience, and no natural law.

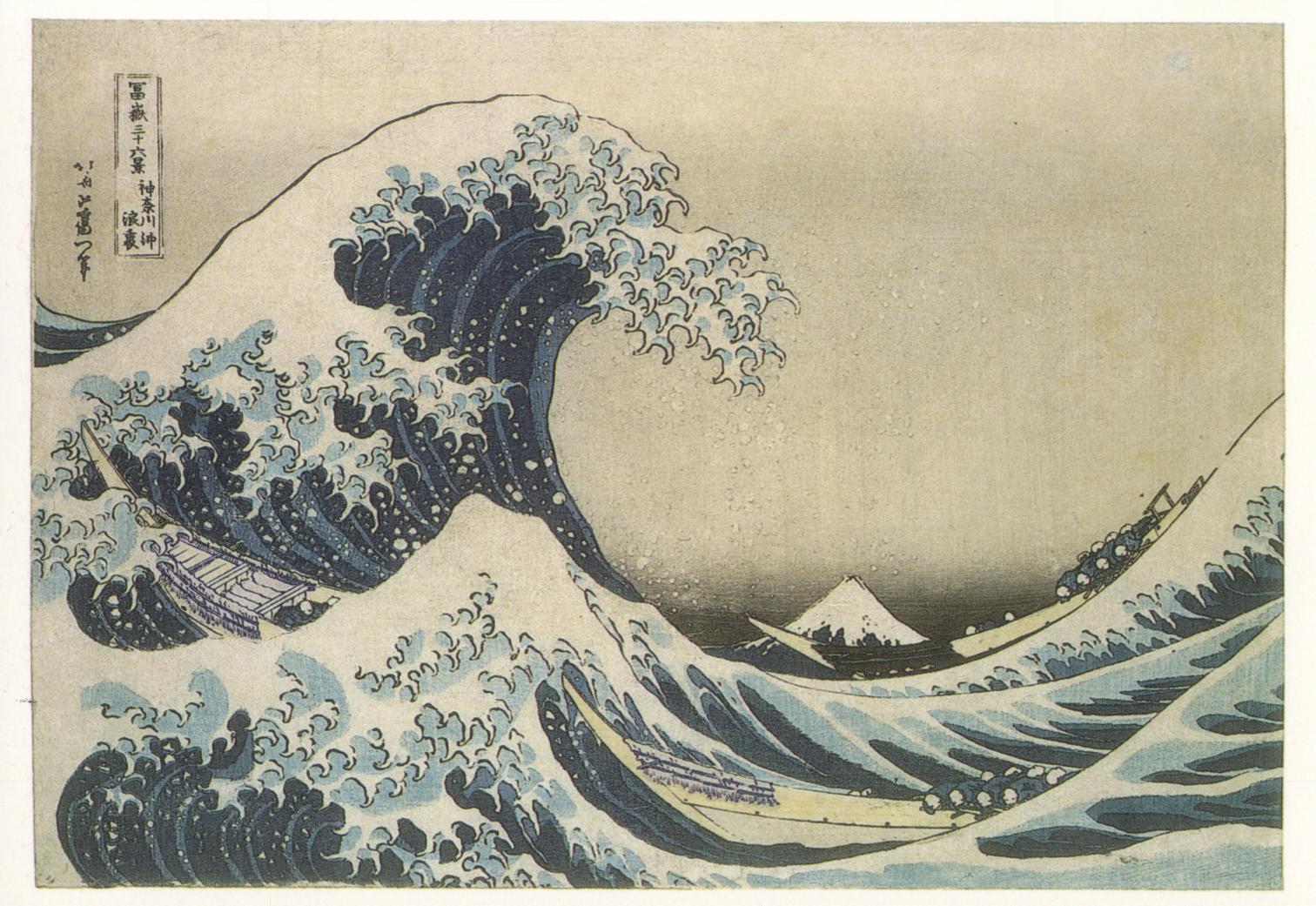

People build society because everyone is alone in their own consciousness. Even people together are alone, buffeted by a sea of sense experience. You can’t hug someone close enough not to be alone inside your mind, adrift in a sea of sense experience, not sure what to trust, with only the skills of pattern recognition to help. That is okay. Even alone, individuals can build society with others. We are obliged to, for our own self-interest.

People are like ships, alien, alone, and adrift on uncertain seas of sense experience, with only the pattern-recognition skills with which one was born, and the rationality developed over time. Yet, from simple threads fashioned from humility and a shared sense of need, a sturdy fabric can be fashioned between individuals, that stands independent of their cultures, to lift them above the rest of the animal kingdom and embrace a peaceful process of problem resolution.

Society can be built projecting forward, in an exercise like linking two ships on a storm-tossed sea.

One ship uses a messenger gun to send a thin light line between ships that the second ship uses to return a stronger line. The process is repeated until the ships are lashed together.

The messenger line is simple: “Can you recall an instance from your personal experience when you thought you were correct but later events painfully proved you to be mistaken?’

Repeating the question: “Can you recall an instance when you thought you were correct and later discovered you were mistaken?” The question nudges one to reflect on patterns of personal experience. Not your experience. Not religious teaching. Not natural laws specific to a culture. The question encourages society with others when question asker and answered discover that they share the common understanding that if sometimes you think you are right not because you are right, but only because you think you are right, that indicates you are not dependent on fallible thinking.

To recognize a pattern of error in one’s own past invariably leads to the conclusion that decisions are made not based on reality, but on a mental map of reality that is abbreviated and necessarily incomplete. The question creates doubt.

Doubt about the accuracy of what one thinks is humbling and a compelling reason to engage others similarly inclined, for the benefit of each. Self-interest and community join.

Insight is a powerful and compelling force. Someone who lies to you does not respect you or your efforts to improve the accuracy of your mental map of reality. Lying is anti-social. The liar has violated the basis for society. Once detected, one has no reason to trust a liar ever again. The insight causes one to recalibrate experience with politics and friends.

This is not a religious doctrine, natural law, or a cultural standard. Yet it is a conclusion invariably reached, even across cultures. While not universal, it might as well be. It is, if anything, a good idea.

Good ideas like this are viral. They easily travel across national and cultural boundaries, generating traction with anyone inclined to consider them. Society transcends culture. Insight about society creates a background by which all actions are measured.

Doubt and the humility it causes are complimentary. One who recognizes doubt becomes humble. Humility comes to those who recognize doubt. René Descartes ostensibly said, “I think therefore I am”, but he was really saying “I doubt, therefore I am.”

Once humbled by doubt, the incentive to manufacture society with others and to the threads of wisdom that are the warp and weft that hold the fabric of cultures together:

Understanding society encourages creation of processes of peaceful problem resolution. Manufacturing society itself allows us to lift ourselves slightly above the rest of the animal kingdom to improve the odds of survival.

The idea that learning literary skills is sufficient for an education is as absurd as suggesting that learning to press the accelerator to make the car go is enough learning for one to drive.

People can deduce shared concepts of Respect and Responsibility from experience. Respect is directed inward towards ourselves and towards our treatment of others. Responsibility is directed outward towards friends, school, community, and world.

Tuned to watch for them, constructive patterns of behavior almost leap out of the past. Such threads of wisdom can be labeled and projected as options for the future to help learn to improve next time. From simple wisdoms garnered from experience, people can deduce that their long-term interests are served by a character-centered life.

These are different from natural law or culture because they come from each individual’s personal experience. These observations are accessible to everyone across cultural and religious boundaries. They foster virtues, a compelling framework for civilization, and a path to honorable decision-making.

Individuals create society for their benefit and humility is as important for groups in society as it is for an individual. Humility represents commitment to the continuous and repeating opportunity for improvement.

Governance with institutionalized doubt has been tried in one form or another in ancient Greece and today. They were not successful in ancient Athens because those governments, instituted for other reasons, fell in part because of hubris: they lacked understanding of its underlying advantage.

Democracy was instituted as a check on consolidated power in Athens. Their faith in democracy was based on one person–one vote and majority rules. The real strength of democracy is that it codifies humility into a permanent appreciation that there might be a better way. It represents a commitment to freedom of speech because the least of us, given the opportunity, can attempt to convince the rest that, whatever the present decision, there may be a better way.

Democracies are susceptible to tyranny of the majority and to buying votes for political advantage. In fact, every form of government can become tyrannical. In a democracy, the capacity to make individual decisions matters. Democracy assures the ability to challenge veracity in front of an audience tuned to judge the accuracy of the argument.41 Brought to consciousness by the charge, individuals choose one side or the other. And, in the end, the penalty for poor reasoning is to have what is said discarded from further consideration.

For those unable to work out the advantage of the minimal behavior of society, a figurative ‘friend-or-foe’ indicator should flash in warning. Society depends on the liberty to laugh at any foolish idea put forward by anyone who chooses to speak. It is not a constitution or a law that protects the laughter, but simple good sense open to anyone who cares to work it out.

A representative democracy, when supported by an education system that works, is able to put forward political candidates with enough character to stand up to a misguided crowd long enough to educate them about what matters. We are prepared to make accessible in classes what matters for students to discover, verify and use.

Recapping, good reasons for being decent and honorable can be built from a foundation of the few ideas already deduced from personal experience. The warp and weft that hold the carpet of cultures together are few — the minimums required for social interaction are few:

Ethics are derived from those understandings. There is nothing more to ethics than that individuals matter.

Likewise, from the two minimums of society, simple wisdoms can be deduced. Simple wisdoms, although common and everyday, are not currently central to curricula and catechisms. While they have been written about for millennia, they have not always been universally taught. Perhaps that’s because teachers are themselves only former students from the same schools.

Dynamic thought processes are the type of thought that matters. Dynamic thought processes help prune what does not work and reinforce what does. If drops of water in a river represent that which is understood, then boulders along the shores that guide the flow of knowledge represent the dynamic processes of thought. Half a dozen simple wisdoms accessible to anybody channel the flow constructively, but we don’t habitually teach such things. They include:

Themes in social studies and frameworks come a point of view that gives students little traction. Students see little in it for them. Across all grade levels and subjects, current courses already contain teachable moments to which simple wisdoms easily attach. Simple wisdoms refine processes used to make decisions. Process matters because, as Robert Heilbroner pointed out, when you master logic, logic masters you.42 It becomes compelling and unavoidable. When you understand that two plus two equals four, nothing will entice you to believe it equals five.

The courage to defend what is important springs from mastering why something is important. Herodotus believed the Greeks at Thermopylae found courage because they valued liberty so highly that they would rather sacrifice their lives to try to preserve it than live any longer without it. Socrates was a tenacious soldier during the Peloponnesian War because he understood his duty. Defending Little Round Top against all odds at Gettysburg during the Civil War, earned a grammar teacher from Maine, Joshua Chamberlain, the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Educators are committed to incredible depth and insight, which they then test with astounding precision: where were these words used in the readings; why were these quotations significant; write an essay on such and so. They test for, and show the course covers material that is fascinating, delightful, complete, in-depth, but nevertheless information, not news. Information may be correct, but news adds context to plan your best future. If core studies leave to chance that which you need to know to plan your best future, you go into the world unarmed.

Basic deduced concepts of society are scalable. They apply to individuals, small groups, large groups, states, and nations.

After the clash of progressively larger groups, estates, states, nations, and civilizations, expect a shift toward the clash of core ideas because those ideas are viral. They can travel across geo-political boundaries with ease penetrating borders of nation-states that are porous to them.

Simple, practical, common wisdoms have been with us for all of our written history. They are found in the works of great thinkers like Confucius, Seneca, Mohammed, Jesus, Locke, Marx, and others. Simple wisdoms are concepts that help us understand where great thinkers made mistakes and why, within the limits of their time, they might have done so.

These dynamic process metaphors apply to our simple daily living. Confucius taught the sense that other people exist, “Don’t do to anybody else what you wouldn’t have them do to you” in the form of the Golden Rule phrased as a negative, and much more practical way of expressing the idea. Karl Marx followed Hegel’s notion that we must constantly evaluate where we are. He fostered a process by which we can examine the way things are; the way we can use time. Unfortunately, and to the pain of millions, after he developed the tool his successors mistook a single iteration, rather than continuous review, to be process.

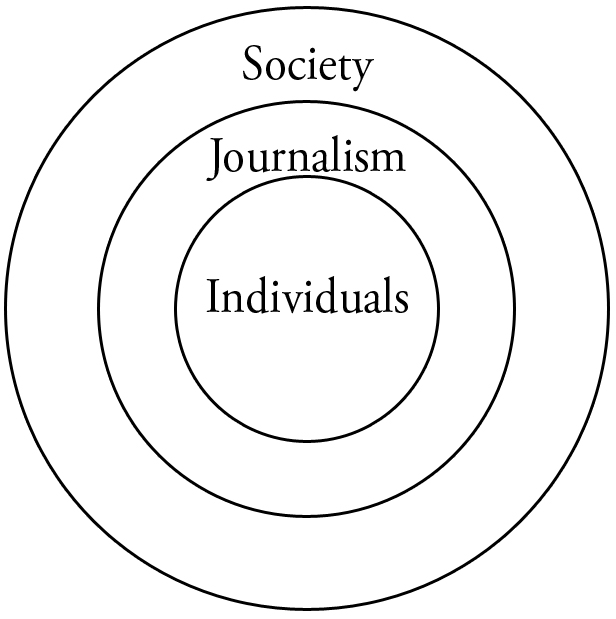

Adam Smith said that we enter into society. In practice, if you master why you as an individual need society, it is society that enters into you. Individuals create society — and journalism, too — out of sheer need. Journalism and society extend out from individuals like concentric circles, and sometimes those creations contain flaws that mirror the flaws of individuals. Those flaws seem to pass almost unnoticed because people don’t see the behavior as flawed.

What is worthwhile for an individual is equally important to journalism and society. Developing the skill to detect the patterns of bad journalistic habits helps detect similar misbehavior for individuals and society. Studying journalism exposes “gotcha” techniques, style over substance, ignorance, misuse of statistics, gullibility, historical amnesia, double standards, misrepresentation, misplaced tolerance, misplaced judgment, silence, politics, overused and underused language, rhetorical games, and logical fallacies. Similarly, the purpose of a discussion is not to win, but to come to understanding.

Dorothy Sayers, the 1930s mystery writer and medievalist said, “For we let our young men and women go out unarmed, in a day when armor was never so necessary. By teaching them all to read, we have left them at the mercy of the printed word. By the invention of the film and the radio, we have made certain that no aversion to reading shall secure them from the incessant battery of words, words, words. They do not know what the words mean; they do not know how to ward them off or blunt their edge or fling them back; they are a prey to words in their emotions instead of being the masters of them in their intellects.”43

Moral relativism’s ambiguity more often leads to amorality than immorality. Immorality requires conscious opposition to what is moral and why. The only mechanism that has a chance to guide understanding for an individual is kept honest by conversation with other individuals in society.

We have the models, metaphors, and experience to succeed, but we don’t seem to value such tools as highly as previous cultures have. It recalls the Roman Peace — the Pax Romana from 27 B.C. to 180 A.D. that imposed the rule of law by force. Actually, it imposed the rule of authority that evolved into a rule of law never matched before or since. They kept the peace, in part, by training people to be good citizens. For Romans, a citizen was defined as a good person speaking well.

Freedom is often mistaken to be a principle. Like other words it has become a cliché used to stop thinking. What kind of freedom are you willing to trade for security? How much of your life do you want a self-obsessed political class deciding for you? Students have to learn enough not to take a teacher’s word for anything. When you lose the meaning of freedom you lose both the reason for freedom and the will to work for it.

Romans had the appearance of freedom. Economically, they were given great latitude, but not at the political level. But other freedoms were at risk:

As with the Romans, who lost their culture, we are busy but have lost our focus. Governance has extended into other areas than the minimal concerns of defense, whether people can exchange ideas and goods with simple contracts that assure the transactions, and a process of peaceful problem resolution.

It is not freedom that we would wish for others and ourselves, but the opportunity for individuality. Freedom is the result of individuality, not individuality the result of freedom. The rest is incidental. It is the freedom to laugh at abuse of power so that others might recognize it and laugh with you until that abuse can get no traction.

Viral ideas transmit experience and history that tempers one’s wisdom and culture. That’s why governments registered typewriters in some pre-computer Balkan states and why later the Soviet state came to realize that a country with computers could not be restrained.

Individuals motivated by strong ideas can influence both people and great nations. That’s good because the future of humanity does not depend on the success of one country but on the preservation of sound ideas and sound processes to think about them, until soil somewhere is ripe for germination. Some Confucian ideas engraved 3500 years ago in scraps of ivory projected good sense into the future. That can happen again.

We must remain alert, since every moment is a potential pivot point — for you, for cultures, and for society. We touch others with sound ideas. Change will more likely turn around a different axis than the pundits expect. One can be touched by ideas as far away in time and place as Confucius whose insight can telescope across unimaginable generations, ricocheting off other minds, to change minds today.

Minds are not always changed constructively. Sorting out unsound ideas becomes every individual’s responsibility. Unfortunately, citizens schooled today often seem unprepared to weigh what they think.

Then again, many ought not trust what they think. Too many people with degrees have not the skill set, attention span, or interest to recognize everyday flaws in themselves, journalism, or society. People like to think they are rational, but fresh evidence arrives every day to question that. Besides, people are not so much rational as learn to use rationality to check ones work.

As explained earlier, we are adrift on a communal sea of individual ideas clawing at each other to grow and survive. Most ideas will be lost, and many should be. The way forward is to sift down not to the true, but to the useful. The purpose of logic and rhetoric, the way it used to be taught, is to serve as a sieve.

Individuals today have the advantage of a world of experience that those in the past did not have. That makes it easier to avoid the tar pits others in philosophy attempted to explore and got caught in. Our predecessors did heavy lifting, but we have incentive others before did not have — the need to act before all society is undermined.

It is too dangerous to be ignorant about judgment in our age. As powerful weapons become more readily available, this becomes a race between civilization and Armageddon.

Mother Nature doesn’t care if we succeed, but we do — we care for ourselves and for our children. Nor can we put off our work, now that isolation no longer offers protection. As Jacob Bronowski noted, science has put the power of knowledge in the hands of anyone who cares to learn, so that no longer will a strong box protect our wealth or barred door protect our families.44 We are in a race that there is no guarantee civilization will win. The competition is to inoculate ourselves to recognize and defend against others who would destroy rather than build society; a race to expand civilization with an accessible, compelling message others might decide to value and adopt as their own.

Happily, civilization has a better chance today than ever before, because all it takes to inoculate people to defend themselves is a change of mind. All it took for the villagers to see that the emperor had no clothes, was a change of mind.

The core of Core is knowledge that leads to patterns from experience. Patterns nudge us to embrace the compelling process to engage in life-long learning mastering the tools by which to proceed.

You matter and you need to discover how much you matter. Then you need to learn to defend yourself. Once you discover that you matter, you can shoulder the responsibility to make sure you are up to the task. The resolve not to be taken in by ignorant, selfish game-players depends on you developing process, pattern recognition, defensive rhetorical skills, experience, and a will to work at it, to resolve. The tools are simple, yours to discover, and yours to own:

Stephen Dedalus in Joyce’s Ulysses was introverted and cerebral, thinking, thinking, and thinking, but not of useful things. He was spent internally, confronting a hostile universe, admitting, ‘History is a nightmare I’m trying to forget.’

Fuse together C3 Frameworks themes 2. Time, Continuity, and Change, 4. Individual Development and Identity, and 8. Science, Technology, and Society, and it is possible to create traction in a single lesson accessible to seniors and even, to a degree, elementary school students who are concerned about what they should do. People often wonder where one should invest time and wealth. As a parallel, one wonders where one learns the equations to balance one’s life.

For context, consider that there are some 6.8 billion people on Earth. Each one is the most acutely interested person of them all from a personal point of view. The universe revolves around each of them. Each experiences the universe through personal senses. But where do others — and everything else — fit in? This calls for perspective, but without reeling and buckling knees. What is one’s responsibility to these 6.8 billion people?

One’s shoulders are not broad enough to carry them all. So, does one give up? How many does one help? Should one help as many as someone else helps? Should everyone tithe?

Socially imposed altruism has others pressure individuals into what to do for those in need while charity is how one decides for oneself what to do. Altruism gives no practical way to answer the question, ‘Do you help one, two, ten, or ten thousand?’ But if altruism is unworkable, one needs to come to personal terms with generosity to create a reasonable, human alternative that puts one’s today, one’s life, and that of others in context.

Charity comes from the one heart and one home, not from government. Dress it up as they might, the tyranny of the few who sway a gullible majority is coercion even when they claim it is for good cause. Worse than a socialist is someone who wants the power to control others to get certain results ‘for the good of the disadvantaged,’ for they are socialists who don’t know their own disease.

Absent government direction, how should one discover a personal charitable balance? From where one stands in space-time, place yourself between the very, very big, and the very, very small. Then, place yourself between the long, distant past, and the unimaginably distant future.

The universe is, perhaps 156 billion light years wide and 13.7 billion years old. Consider where an individual fits in:

Humbling, isn’t it, to know your consciousness fits in between 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 meters and 0.000,000, 000,000,000,1 meters, and between 13,700,000,000 years of history and an infinite future, among a world of 6,800,000,000 people, many of whom are in need of help.

That could make one feel small, but it puts each individual in charge of that single point in the universe that is the center of their unique consciousness at this one instant in time, gifted with the will to make decisions. Whatever its physics, the center of the universe is here, now, where an individual meets it.

Just as you are in charge of your point of consciousness, and I of mine, others are in charge of theirs. It is your responsibility to defend your point and path from others, and, reciprocally, resist the temptation to impose your trajectory on them. You can teach, but you cannot rule, except insofar as they violate the minimums of society. Now, consider how one decides what to do.

Decide first whether to give up on altruism. Altruism is a premise whose time has never come and never will because it is too easily used as a club by others for their own interests. One has no obligation to help others — although those who would take advantage of an individual for their own reasons may try convincing them that they do. Instead, recall Charles Dickens’ Ebenezer Scrooge after his epiphany. Scrooge’s new perspective on his own existence led to reverence for the situation of others. More alert to one’s own journey, one is more sensitive to others, which presents opportunity and personal interest in charity.

Few people, if any, read Adam Smith‘s first book, Theory on Moral Sentiments any more, but he recognized that altruism was not an effective virtue. Self-interest brings the truth of experience and, ironically, can be more effective at prompting people to help others. That may sound ridiculous and contrary to observation in today’s selfish world, but Smith described a principled position not to be confused with unthinking consumerism.

So who did Livingstone, Schweitzer, and Mother Theresa do their work for? Not the poor. That’s the conventional wisdom, but they worked for themselves. Joseph Campbell advised people to follow their bliss. That’s what Livingstone, Schweitzer, and Mother Theresa did. They put themselves where they felt they belonged.

Central Africa, India, or our poorest neighborhood may not be where you belong. Your teacher can’t tell you. Neither can your parents. It is not a role someone else can press upon you. Not altruism, but your own inquiry into yourself will lead to your particular answer.

Approach it from a different way. For each of these questions, figure how far along a continuum you’d place yourself:

Along the X, Y, and Z axes an individual can, respectively, place answers to those questions. There is only one location in the graph that describes one’s unique comfort zone for today. It will be different on other days and different for other people. Certainly there are more questions and axes possible, and all of them challenge one to be responsible for setting the mean between the extremes, one’s balance point Aristotle called the virtue between the vices. For an individual, the balance point for each question can change over time. The task is not to put oneself at the center of one continuum or another, but to understand where, along each continuum, is the healthy, comfortable place for one to be.

And if, among the considerations, one finds bliss tending to a garden, tending to family, tending a neighbor, tending to community, or tending to the world, at that moment, that is where one belongs. If it is in the heart of Africa, at a soup kitchen at the Welcome Hall, teaching, writing, or coaching Little League, or simply loving family or friends, go for it! It is not the job of someone else to shame one into altruism. How dare they try!

When you are at peace with your place in the universe, when you are in balance, one will find that Kant’s concept of duty is not the powerful motivator. Reciprocity — the sense that others live their lives as acutely as you live yours — is a powerful motivator to help and share, and you’ll find great joy in it.

This is a recap of material mentioned above, but worth the repetition: In your own experience can you recall painful experiences that occurred because you thought you were right and later discovered you were mistaken. These points are accessible to everyone across cultural and religious boundaries. Using them we can fashion virtues, a compelling framework for civilization, and a path to honorable decision-making.

Point 1: Sometimes we think we are right, not because we are right, but simply because we think we are right. It’s possible for you to be wrong, even when you think you are right, because your brain — the tool you use to plan your very best future — decides what to do using not reality itself, but its very own internal map of reality. If that map of reality is inaccurate, you can get hurt.

Point 2: Your long-term self-interest depends on maintaining the very best map of reality to work with. Even though other people have different experiences from yours, they can recall their own painful experiences that invariably lead them to the similar conclusions about humility and reciprocity.

Point 3: Those other people live life as acutely as you do. They have the same needs with reason to join together in society. Society becomes mutually beneficial so we can help each other refine our individual mental maps of reality.

Point 4: Reading, writing, and conversation hone skills used to better individual futures. Language is the tool we use to maintain our map of reality, to check it, to refine it, and to represent it on paper so that tomorrow we can look back and see if it makes as much sense then as it does to us today. They capture our expressions of concepts to convey them over immeasurable distance and time to others. Quality of language and its tools matter. The Trivium — the first three of the Seven Liberal Arts — refine our tools.

Point 5: A sense of time and one’s place in it provides a check on one’s map of reality and decision-making.

Point 6: Thinking about thinking is a powerful tool that needs to be harnessed to be constructive.

Point 7: people are responsible for themselves and need to take that responsibility. As children connect language and thought, they are empowered and motivated by Simple Wisdoms that underlie their conversation:

Dynamic processes are the type of thought that matters. They help prune what does not work and reinforce what does. If drops of water in a river represent that which is understood, then boulders along the shores that guide the flow of knowledge represent the dynamic processes of thought. A handful of simple wisdoms accessible to anybody channel the flow constructively, but we don’t habitually teach such things. They include:

These are processes kids understand, admire and wish to emulate in a deeper way.

The evidence of writing is that humans acquired consciousness over time and not in a single cataclysmic event. Some acquired it, some did not, and, unbelievably, some cultures lost the skill. While there are a lot of things that consciousness is not, Julian Jaynes holds consciousness to be a very simple thing that includes:

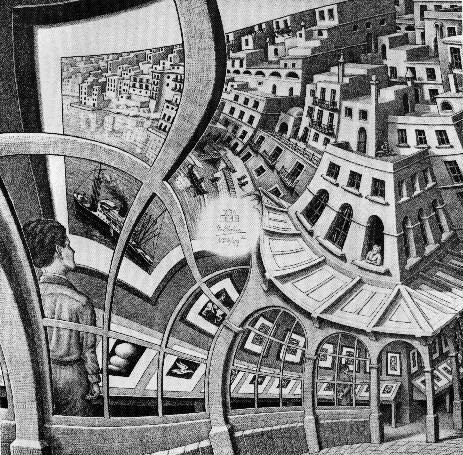

Douglas Hofstadter suggests that the emergent phenomena of the brain–those are ideas, hopes, images, analogies, and finally consciousness and free will–are based on a ‘strange loop’ that we have learned to call recursion, an interaction between the top level reaching back into the bottom level and influencing the thought process for succeeding iterations.46 M. C. Escher’s Print Gallery is a visual representation of the recursive process.

Thinking as we have been talking about it — conscious thought — is acquired. Self-reference is acquired. Narratization — the ‘I will do this, then I will do that’ — is acquired, reinforcing the concept of time, one’s place in time, and the concept of recursion. Narratization is what Lucy Calkins teaches in her Writing Workshop, even to students in Kindergarten.

Experience, process, pattern recognition, defensive rhetorical skills, practical experience are all dynamic tools one uses to make more accurate one’s mental map of reality the better to make decisions and the better to defend oneself against what is destructive that people, including oneself, might propose.

Useful processes and experience can be mined from what has gone before. Ibn Khaldun wrote on historiography, discovering in the flaws of earlier historians the need for humility. He emphasized Hegelian or Marxian dialectic — feedback loops — a process of continuous re-evaluation necessary because — and this is the keystone of wisdom — sometimes we think we are right simply because we think we are right.

Negotiating our way through life, we are interested in the simple daily problems of living such as dealing with people and dealing with the loops that we get into in our own minds. Loops that we have described happen every day in thought. We’ve learned not to blindly trust what we think simply because we are the ones who think the thought.

Seneca, writing about 50 AD admitted he read the opposition because he presumed he had no lock on truth. To disagree with one’s opposition, one has to know why and to have reasons that stand up to scrutiny for the positions one takes. Rationality was a standard during Voltaire’s Enlightenment. It proved insufficient. We need to be more than rational. Rationality is a tool to encourage consistency in what we have thought. Simple wisdoms from experience encourage process and perspective to help make the simple daily problems of living more manageable.

Our goal is to lift ourselves just that much above the rest of the animal kingdom and the law of the jungle, to manufacture an umbrella to protect us using a process of peaceful problem resolution that others learn to trust and embrace in their self-interest as their own.

The frameworks consider rules and law to be an enduring understanding. Confucius considered that the last refuge.

Confucius believed there were three kinds of people:

Because the frameworks value order and following rules so highly, they fail to encourage others to achieve higher understanding. They play to only the lowest capabilities, supporting order imposed rather than order individually understood and voluntarily applied.

One needs to tell constructive ideas from destructive ones. Then one needs to inoculate people to defend themselves sensibly.

That first calls on Karl Popper, the philosopher of science, who reminded people that science is not about truth, but about doubt. Science is a test for falsity that helps prune ideas that don’t stand up to experience. Otherwise, in one kind of arrogance, people become convinced that their own ambitions are worth the suffering of others. What is true one cannot know, but science helps one understand what is not true.

One ought not be wedded to one’s own ideas. Be wedded to sound ideas. It is important to learn where one might be mistaken. That allows one to make decisions based on the best information available. Michel de Montaigne, inventor of the essay as a literary form in 1585, said he would run to embrace truth from others when he saw it coming.47

The problem is systemic. People used to learn to discuss in schools, once upon a time, when it was taught in the seven Liberal Arts as the Trivium — Grammar to put your thoughts in order; Logic to see if those thoughts were consistent; and Rhetoric to explain those thoughts clearly to others and analyze their replies.

We hinted at morality earlier. The traditional foundations of ethics and morality need not be found in religion or natural law. They may get in the way. The foundations of religion and the so-called eternal truths are the business of cultures that operate on top of the framework of society. Morality springs from the minimum behavior required for society. Mother Nature will not care if our schools do not see that. But we do — for ourselves and our children.

Among the things that distinguish between ourselves and others of the plant and animal kingdom are the skill to communicate complex ideas to each other and the potential to project the ramifications of plans for the future. If we do not exercise these skills, we revert to the level of others in the world of nature — governed by the rules that nature requires and nothing more. Be human or be no more than an animal. The choice is individual.

Most other animals are outside the framework of morality. Morality is purely a creation of thought. A seal that snips off the fins of a fish, leaving it a terrified, living, helpless toy to be batted around until boredom and hunger make it lunch, has no conception of good and evil. Good and evil don’t exist in the world of seals and fish; life is simply the way things are.

Morals are integrally tied up with the immediate practical protection of one’s own life. My proper concern is my own life. Your proper concern is yours. The future safety of any individual is integrally tied up with convincing as many other people in the world as one can the value of living under a moral umbrella that is equitable and valuable for wellbeing, and by actions that decide under what conditions they will be treated. Our own best interest is to encourage the kind of thoughtfulness to understand the ramifications of individual actions.

Not everyone will be convinced. No compelling reason in the laws of nature or mankind will irrefutably justify morality to any and all men. One who chooses to act by the laws of the lion need not even consent to listen to the arguments in favor of morality. He need not choose to heed anything but that which compels itself to be heard by the laws of nature, if even that. People cannot be forced to join together under the protection of a moral umbrella; we can only encourage them to do so by presenting its advantages and encouraging them to develop the thought processes necessary to weigh them. Our own best interest demands we help as many as possible to become so thoughtful they clearly understand such things. Our security depends upon it.

People don’t have to sign up as if it were a contract. An individual does not so much explicitly subscribe to protection under the moral umbrella as reject it by an explicit act. The minimums of society are few. Restriction of the freedom of communication, such as muzzling free speech or press, or hostage taking amongst the diplomatic community casts one out from the umbrella’s protection to put them at the mercy of the laws of nature. By such action one opens oneself to any response in the arsenal of the laws of nature we may choose to take. He has chosen the battlefield, not us. We, in turn, are subject to the laws of nature in our response. We need not reply using the standard of the moral umbrella the offender has rejected, although we may choose to do so. Pacifists and generals of quality understand that war is a nasty place to be and should be avoided, if possible. But those of us who understand morality reserve the right to protect themselves by any means necessary. And one might survive or both might die. Nature does not care.

If students of today are to escape from moral relativism to establish minimum standards of behavior then they have to go beyond the language that limited the brilliant Socrates. Where Socrates had only the word polis, today’s students can differentiate polis from ‘city,’ polis from ‘culture,’ and polis from ‘society.’ Our language lets us see more clearly than Socrates could. His notion was that if one looked at the polis that mankind created, one could project backward to gain insight into the make-up of an individual. The single word polis did not differentiate between culture and society, which led to notions about the individual that do not follow. Because individuals create society, notions deduced about the individual do provide insight about society.

Plato proposed rules 2300 years ago but no one could prove their universality. Churches, which typically depend on rules and examples demonstrating them, have difficulty getting the message across to others beyond their faithful who already are convinced. Campaigns based on religions don’t convince, they compel, with no less power than Machiavelli proposed 600 years ago to coerce people to behave. The conundrum of how one should behave has thrown us into a downward spiral of moral relativism that resigns ethics to “might makes right.”

Some believe, as St. Augustine wrote, virtues are written on the fleshy tablets of the heart as some kind of natural law. Natural laws are culturally dependent and cannot be proven to be absolute.

P. J. O’Rourke referred to Richard Brookhiser’s biography of George Washington, Founding Father to explain how people looked at things differently 200 years ago. ‘We worry about our authenticity — about whether our presentation reflects who we “really” are. Eighteenth century Americans attended more to the outside story and were less avid to drive putty knives between the outer and inner man. “Character” . . . was a role one played until one became it; “character” also meant how one’s role was judged by others. It was both the performance and the reviews. Every man had a character to maintain; every man was a character actor.’

Children and adults today can live by the 18th century standard where character was a role the immature would play until they discovered through life experience what constituted real character. The alternative is to establish a solid foundation of process concepts that lead to character among those capable of grasping it. Experience can reveal patterns that, if we choose to recognize and think about them, can give us insight into a more advantageous way to think.

Humility and reciprocity are the foundations from which to deduce morality.

Real morality is not culturally dependent. That is yet another instance where one word represents two flavors of behavior. Separate words do not exist to distinguish between culturally dependent traditions called morals, and process concepts — morals deduced from humility and reciprocity that are the minimal requirements for society.

Concepts considered virtues map to process concepts:

Other so-called virtues are skills like rhetoric or worthwhile habits like creativity, orderliness, or endurance. Still other useful understandings are important to know but are not usually classified as virtues:

If one were to try to find a word to distinguish cultural mores from societal morals, the word “character” fits the morals deduced from humility and reciprocity. Character represents the processes one mind uses to decide how to act toward others.

Also consider where the courage represented by the Hobbits in Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings might come from. Characters in books find a well of strength to draw from as surely as they find it in real life. Thomas Mann’s hypothesis in Magic Mountain does not have to play out, that our culture creates people that are docile and compliant. Docile and compliant isn’t courageous. Joshua Chamberlain at the battle of Gettysburg was courageous, not docile and compliant.

Suppose that virtues like kindness, wisdom, and integrity do develop character, one has to decide what virtues should be taught.

The nagging question is how to know for certain that the virtues one would teach are true virtues. Wealth or fame are popular yet not likely to be considered virtues.

Virtues have been described as those traits cultures value. To discover them, one could go with what has worked and accept what has gone before as gospel. But which gospel from hundreds of conflicting religions and sects should one accept on faith? Perhaps the one you believe in, simply because it’s yours? George Bernard Shaw sarcastically asked in 1919, in Heartbreak House, “Do you think the laws of God will be suspended in favor of England simply because you were born there?”

World War I dashed any vestige of belief that liberal values and technological advancement in natural sciences would lead to steady, civilized society. The world was left in wreckage with cultures in conflict.

Suppose one decides to adopt that which other cultures discover to be virtues if they add value — however that would be measured — or that further a culture. One still would have to fashion a virtue detector.

Reflective judgment is called for, not compliance, to remain continuously open to new information to review that which we have learned regarding what has gone before in light of what we might better understand now. Since politics has become cutthroat competition, people to develop the skill to test its claims. Philosophers say that all knowing comes:

People need to recognize the authority that underwrites the knowledge and value it accordingly. We may not be able to decide what is ‘true’ but we can consider what might be ‘workable.’ To draw on the canvas of the new century, all we have are recollections and patterns recognized from them, massaged by language within its limitations, we can use to project consequences of proposed actions into the future.

You can only discover if what is asserted as true does not match patterns of experience. As was said earlier, Karl Popper explained that science is not about deciding what is true, but embracing a continuous process to identify and reject what is demonstrably false. Phrased another way, society is at risk without the freedom to say something someone may not care to hear. That said, the freedom to offend does not imply the necessity to do so or determine the form it might take.

When deducing morals, process concepts encourage thinking about yourself, your place in society, and life itself. A path seeded with process concepts offers practical help that people can easily embrace that ultimately leads to virtuous behavior. Process concepts ignite the spark of self-regulated learning that just this easily pass Socrates’ torch on to the next generation.

Journalism is the perfect vehicle to make these essential concepts accessible, and is a division of labor that, for usefully serving individuals and society, would have pleased philosopher Socrates in ancient Greece, sociologist and historian Ibn Khaldun in the Islamic empire, and economist Adam Smith after the modern industrial revolution. As a surrogate for the individual, journalism fits neatly in a concentric circle between the individual and society.

One could defend frameworks for not answering every moral concern, but doing their part to help. That is as if their boat is turning in circles, with oarsmen rowing only on one side, but they are satisfied with their progress.

The problem of how to teach character is very old. Socrates died for it in 399 B.C. In the 1700s, Immanuel Kant wondered, why it was that moral instruction accomplishes so little. Yet, he observed, even little children understand that you should do a thing just because it is right. Our challenge is to go beyond rewarding good behavior, which Kant recognized was ineffective, to do that which Socrates called not ‘teachable, like geometry,’ but teachable in a way, that we might produce not docile sheep but responsible, growing, inquiring citizens.

Some 2500 years ago, around the dawn of civilization, Confucius thought about the way one should behave. He called it li, which is Chinese for the way. He determined there were those who intuitively knew the way to live — natural saints, as it were. Then, he believed a second, larger group of people could learn the way. He considered himself in that group. The remaining group of people required fixed rules of behavior he called laws or ritual.

Fixed rules are directed to the third and least capable group, leaving others without instruction to master the more useful skills. As many people as possible should be encouraged to join the group that learns how to figure out the way — the group that isn’t just told the way to live, but constantly considers whether their personal choices are honorable.

Everyone deserves to be put the question why they should choose a character-centered life. That question really asks why is such a life in one’s own long-term best interest. Professor Peter Kreeft in What would Socrates Do? pointed out other questions, too.

One approach still in use is to teach the vocabulary of character. Promoters of the rote learning of virtues in the classroom proudly show videos of small children happily singing about character. Happiness in the classroom does not guarantee success. Sometimes children are just entertained. The net result in later years shows no great progress.

The question is whether having respect develops character or whether character lead to respect. That raises the question does obedience result in character or does character result in obedience.

If virtues are what should be taught, then there should be a clear path to explain how one gets from the vocabulary to character. If teaching virtues does not effectively develop strong character, another method is needed to develop strong character more effectively.

Virtues may be laudable and rote learning is easy to teach, but to teach someone to ‘Be this way’ or ‘Be that way’ attempts to teach the result you want to achieve, absent the process to get there.

People who know the vocabulary don’t necessarily act with character. Complicating that, the virtue presented doesn’t necessarily apply to the situation. Virtues like ‘respect’ and ‘obedience’ sometimes lead to the wrong result. Suppose ‘respect’ is not deserved. Suppose, authorities demand action that would be unethical, in which case blind obedience would not be a virtue. ‘Obedience’ is important, until it comes into conflict with other virtues. If teaching just virtues leads to lack of character, there needs to be a way to determine the difference.

Those in favor of social studies will suggest people need to learn to exercise judgment, but courses propose to teach vocabulary, not judgment. The practice of teaching the vocabulary of virtue may not develop character by any means other than chance. Learning virtues is different than developing virtue.

The long track record of teaching virtues shows that children react positively to such a program. It’s delightful to see schools of smiling children happily singing along in the promotional videos. Teachers vouch for participation, but that doesn’t indicate success. Teaching that way is immediate and easy. Downloadable lesson plans promote the vocabulary of virtues. Definitions are easy to test. Essays that explain why a role model demonstrates one virtue or another are easily graded.

Character certainly isn’t promoted through character vocabulists plastering posters in public places. Consider the posters that are hung:

That is a platitude that masquerades as wisdom. Who are those served, and why should one commit to them? Commitment became a liability during the Nuremberg trials after World War II.

That is stretching to find both the vocabulary and the definition.

To decide what is right is left as an exercise to the student.

Character vocabulists can walk right by insight, never notice the gold mine, and manufacture trivial tributes for any fine sounding adjective. New ones can be manufactured that are as fact-based as anything else offered:

Far from promoting ‘Character’, virtue-promoters want the warm feeling they get when they convince themselves they promote character. Results don’t matter. The number of posters posted matters more. If enough posters are posted, those who need character must get indoctrinated.

They think mastery of the vocabulary of virtues is character. Virtues to them are like numbers trying to substitute for mastery of arithmetic. ‘Seven! Seven is a good number! Learn seven and arithmetic will certainly follow. Five! Five is another worthwhile number. Master seven, five, and several more and arithmetic will magically appear.’

Numbers and arithmetic are not the same thing. For character vocabulists, if one learns to define the words of character, mastery must be just around the corner.

If to encourage character, one holds up exceptional people to emulate, like Luther Burbank, Martin Luther King, Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, should one emulate their actions or emulate how they decided to act?

“How does one decide who to emulate or what trait to emulate? Emulating virtues leads to the appearance of virtue, not to the solid processes that lead to virtue. Solid thought processes lead to compelling understanding why virtuous behavior is worthwhile. Persistence shouldn’t be emulated because Washington had it. Persistence comes from understanding what is important and why. Teach virtues alone and we risk overlooking the need to nudge people toward recognizing for themselves critical processes of thought. People teach the result they want but not the skills to get there.

Perhaps character education is only taught the way that it is because alternatives have not been clear. Virtues are the result of thinking about yourself, society, life and your place in it. Our job is to seed that path with a handful of process concepts that allow people to help themselves.”

A virtue is a shorthand label for the result of thoughtful analysis about a general concept that is, itself, easily acceptable and easily understood from one’s own personal experience. Process concepts help people decide what to do so they can plan for their better future.

People insist on trying to push character onto others when much of the real work — the work inside their own head — remains unfinished. If you think you know what to do but don’t know why, then you don’t know character, much less how to convey it to someone else.

Youngsters may have to be guided by rules until they mature enough to come to see the practical value in it for themselves. They need to develop the skill to consider points of view, and to value thinking as a tool for self-protection. Such thinking is only now reentering the curriculum. They also need an opportunity to practice and to see it in practice. Character is not a habit but, rather, a skill honed with practice.

Those who want order teach people to behave — to follow the law — but that does not promote character.

Socrates’ Apology was about order versus responsibility and discipline versus free speech. Those who are afraid of speech don’t trust people. They don’t trust anyone other than themselves, and yet we are supposed to trust them? For what reason?

Socrates asked the question ‘Who has the right to educate students?’ which is really the question ‘Who governs?’ You call it order, but it is about who governs, and order is not judgment. What are these children to do when you are no longer present to exercise your judgment for them? Character is not about applying rules. It’s about being able to make complex life decisions — and to understand and justify them. This is not easy. Sure, people can fake character by following rules for one reason or another, but Descartes called rule-based living a magnificent temple built on a foundation of mud. Those who live by rules have no certain criteria for determining good and evil. Kreeft reminds us that an act is good because of the principle that motivates it, but rules aren’t principles.

This stew caught recent philosophers who resigned themselves to believe morality is relative and therefore ineffective for organizing society. Relativity is irrelevant if views are expressed in a framework that others recognize will hold equally true for themselves.

Frames of reference, constructed from similar experience, while not universal, are as effective as if they were universal. How to act can then be explained in terms even the culturally distant understand and can believe.

Developing character has to be a two-step process.

For example, it is possible to identify with Montaigne who wrote, “If a man remembers how very many times he has been wrong in his judgment, will it not be foolish of him not to mistrust it ever after?”

Given such embarrassing and sometimes painful similar personal experiences, that would that lead one to mistrust one’s judgment. So cultural relativism does not preclude developing that shared understanding.

Montaigne’s personal experience certainly is distant from ours, but one can identify the same pattern in your personal unique experience. Montaigne shares a frame of reference despite extreme differences in religion, language, upbringing, culture, time-shift, and almost everything else. Montaigne and people in general can go beyond the traditions that only carry them so far.

People seem adrift, infected by moral relativism — the idea that moral judgments are founded in cultural background which implies that what is considered proper behavior for another person differ from our own opinion. What appears as lack of morality is the hollow framework of earlier philosophers crumbling under the heavy weight of more recent criticism like Friedrich Nietzsche’s ‘God is dead’ and Jean Paul Sartre’s nausea at discovering a universe both Shakespeare and Faulkner called “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” They found nowhere to turn.

That left authorities to beat the same drum louder and harder, with no greater expectation of success, to hand out binders full of character notes that miss the mark. They trundle out credentialed experts whose lofty and traditional words mask their limited success. It is easier but less useful to drum into our students a fixed set of rules, or we can help our students develop a process by which they can decide how to respond honorably. That takes more effort, but it produces better citizens. They are better able to recognize the ethics of a situation they find themselves in, and to decide how to respond appropriately to those circumstances.

Across the better part of a millennium, the institutions of governance challenged to raise human society have instead sown the seeds of their own destruction. Look at what has not worked over the centuries:

Each refinement of governance failed to clean up the mess left by the previous century and left a different mess for the succeeding century to deal with. In our time, and most unsettling of all, institutional subjects like history, philosophy, art, science, language — the subjects traditionally used to compose alternatives — have themselves become suspect.

The 20th century was an incredible century advancing the sciences — chemistry, physics, biology, psychology, geology, and archeology, engineering, electronics, set and graph theory, gaming, and computation. But socially, we deal with each other much the same as we have for a hundred years: unable to explain that a different culture was destructive or explain why. In the 1990s, in a Post-colonial world, we failed to detect threats when challenged, answer objections to facing those threats, or frame our conclusions in a culturally independent fashion. Our forefathers tried to codify John Locke in the American Constitution, but, until now, the reasons why we ought to preserve those principles have remained elusive.

In the 20th century, morality never grew beyond Machiavelli and politics became what you can get away with. The ‘-isms’ that come to mind — Libertarianism, Conservatism, Classical Liberalism, or any of the political parties — have not inoculated individuals to defend themselves. Nor have they countered the political class with an alternative that values the individual and explains the tie between individuals and society.

You cannot value what you cannot see. If you can’t see why individuals need society, manufacturing society will remain unimportant. It’s not hard. It’s just not habit. A person keyed to search for a pattern in personal experience is more likely to recognize when that pattern shows a useful way to behave.

A pattern gives you a tool, not a rule. It does not insist how you should behave. The puzzle exercised the notion that practice to recognize patterns in personal experience is also useful with governance, thought, language, ethics, and culture. Practice and you’ll learn to project the consequences of actions into the future and learn to put yourself in the position of others.

But there is more. People trust their own judgment, when they know it has failed in the past and will likely fail again. They trust thinking machinery that jumps to conclusions and that tries to justify those conclusions by the flimsiest of means. If one can’t trust oneself, how can one trust others equally likely to jump to their own conclusions? Conversely, how can they trust you?

It’s humbling on all counts, and for their mutual safety leads honest brokers to invest in society and the tools for clear thought.

If we eliminate what has never worked and never will, it leads us to conclude that, individuals alone, adrift on the storm-tossed sea of experience, are obliged to discover who else, also adrift and alone, might, by their actions and not by contract, participate in a social safety net strong enough and reliable enough that, while imperfect, can lift participants modestly above the rest of the animal kingdom. The odds that fortune will bestow its gifts need to improve only slightly to give realistic advantage.

We have filtered the best of what has been said and thought out of education. Where do you learn to work the complexity of life? Montaigne, when he despairs of making sense of himself speaks to the internal complexity with which every individual must cope. “All contradictions may be found in me — bashful, insolent; chaste, lascivious; talkative, taciturn; tough, delicate; clever, stupid; surly, affable; lying, truthful; learned, ignorant; liberal, miserly and prodigal: all this I see in myself to some extent according to how I turn — I have nothing to say about myself absolutely, simply and solidly, without confusion and without mixture, or in one word.”

And where do you learn to struggle? The myth of Sisyphus tells how the gods condemned him for all eternity to roll a boulder up a mountainside only to have it tumble down again just before it reached the top. The myth is a metaphor — a fiction that tells a truth. In his interpretation of Sisyphus in Once and Future Myths, Phil Cousineau reminds us of something every generation has to learn for itself: It is not what happens to us that matters; what matters is our attitude towards what happens.48 The story doesn’t ennoble suffering, it ennobles struggle. Struggle is inevitable, and those who learn to see it as an obstacle rather than a burden make life a lot easier for themselves. Cousineau concludes, ‘the secret of the creative life consists in taking the next step, doing the next thing you have to do, but doing it with all your heart and soul and finding some joy in doing it.’ If you forget all the facts and formulas you learn in school, you will nevertheless have grown to be an educated person if you shun the self-absorbed, downward spiral of suffering and develop in yourself, instead, the will to apply yourself each time you approach the mountain.

We clutter the curriculum when the central subject worth teaching is how to live.

Our country is exceptional because it has confidence in its citizens. Confidence in “We, the people” was and remains the singular most important revelation about the founding of our country. As a corollary, education is not used to achieve power or to maintain it.

Until now.

It is disturbing to hear the most powerful advisers in government to suggest that manipulation of citizens by government is okay.49

Yet that is precisely what K-12 frameworks appear to do. The giveaway is the studied integration of social studies examples into the ELA program replacing the use of literature that also examined the relationship of individuals to cultures and society.

It is an inversion of the relationship of citizens to their government from which the founders of the country sought to insulate us.

The goal is not to mold students into being “college and career ready” nor is it to become “good citizens.” The goal is to develop maturity and independence that lead one to value and guard society.

The Greeks valued liberty, and for that liberty were willing to sacrifice everything rather than give up. Too many today would casually trade in liberty for the empty promise of security and the certain slavery of a free lunch, never appreciating its true price. Ours is a generation so free that it has lost the meaning of freedom, the reason for freedom, and the will to reach for it. As surely as people who have no liberty yearn for it, the people who have liberty handed to them lust for absence of risk.

Politics wrestles with the question, “Is there room for the individual in society?” That question was put to bed a century ago, and certainly put away during Ronald Reagan’s confrontation with the Soviet Union. After years of dullness and lack of vigilance, the question has been resuscitated. Rephrase the question and people become uncomfortable: “Is society a user of people?” and “Should individuals be suppressed for the advantage of society’s powerful?” Individuals need to carve out space in a dominating society. Technology has blinded you; you are connected but not social.

Philosopher Erik Erickson asked the meaning of life. Say to anyone who asks, “You selfish, egotistical bastard! You sit there, surveying the world from a very pretty perch, indeed, provided you by everyone who has ever gone before. And you dare to break the gift they have given you. You contemplate abstracts self-indulgently, complain how hard you have it, and that there is nothing to live for, when you cannot see the gift you have been given. You rush to escape, into drugs, alcohol, television, hedonism, small talk, self-pity — anything to stop looping in your head or facing the reality of the meaninglessness of it all. Oh, the horror! Well, grow up! You may not find meaning, but meaning can find you. Your job is to get out of bed, no matter where that bed may be, and say, ‘Damn! This is a wonderful day, and I’m going to make the most of it. I am going to laugh, cry, and work myself until I’m happily tired. And, by God, when I die, someone will be able to look back on what I have done, and say thank you for clearing my path just a little more.’”

Uncertainty — that is what we are given. Certainly, we are alone, but we are also together. Sartre reminded us that, although alone, we still have those that we love on whom to practice loving.

Society is so simple, but I is not understood easily or often because appreciating ‘why society’ takes more steps to independently deduce than it takes steps to see clearly once society’s simple elegance is pointed out. Besides, as you have already seen, society is easily and often confused with culture.

Once you do figure why society matters, you can sell the personal advantage society offers others, and, furthermore, you are armed with the tools and the courage to defend it against those who, resigned to living just the law of the jungle, would destroy it.

To protect society, you need to know what it is and what it does. That arms you to detect and label behavior that would undermine it. The first weapon of choice is laughter, but every weapon in the arsenal is available to those who would use every weapon in the arsenal against you. Speak softly, but carry a big stick. Keep the big stick but keep it sheathed if possible because you can’t predict its unintended consequences. In the end, use the tools you’ve got. As explained earlier:

People have every reason to hope. Just as Confucius’ carvings on some ivory could reach out to touch someone 2500 years later, any insight recorded now can reach out to touch someone else in the unimaginable future.

Congratulations! Individuals get to disperse the creeping fog — now that they can survey the past centuries in coffeehouses, work, journalism, art, education, character, individuality, politics, economics, advertising, history, academia, religion, literature, language, community, and culture. Now, you make your own hope.

In summary:

Local school districts have been handed a pig in a poke. The pig has been gussied up with lipstick in the form of some needed attention to basics.

While teaching techniques have been refined over the years, with or without Common Core, content has been pedantic, cumbersome, disorganized, and shallow. The resulting disaffection opened the opportunity for revisionists to slip in pedagogy and content that promotes unapproved social transformation.

The tactic is not new. Ibn Khaldun sniffed it out 700 years ago:

Throughout history many nations have suffered a physical defeat, but that has never marked the end of a nation. But when a nation has become the victim of a psychological defeat, then that marks the end of a nation.50

The good news is that labeling the condition sets the stage to defend against it. If locals reclaim education from mistaken over-centralization, the resulting competition of ideas could be very positive.

In the fable, it was the voice of a child in the company of the professional entourage who suggested that the emperor, parading in what he supposed was his finery, was wearing no clothes. As common folk recognized the case, all the fancy crumbled under the weight of laughter.

Laughter is wonderful. It means we have discovered a better way of seeing our world. It means we have learned enough to do better, if we have the spittle for it.

Educating Stability Table of Contents

Next chapter: Educating Stability: Appendices